This article was first published in CUFI UK’s Torch Magazine. For the latest issue, click here

The stunningly beautiful island of Alderney is a British Crown dependency and the closest of the Channel Islands to the UK (60 miles). With an area of just 3 square miles, sleepy Alderney boasts idyllic sandy beaches and rugged cliffs, with playful puffins and hardly any tourists! But in 1941, this remote corner of the British Isles, blessed with sunshine and the gentle splendour of creation, was cast into the evil shadow of Nazi Germany and became the location of the only concentration camp on British soil.

Described as ‘the last stepping stone before the conquest of mainland Britain’, almost the entire population of Alderney (about 1,500 people) gathered en masse at the quay at Braye Harbour on 23 June 1940 after being given just a few hours’ notice. They were evacuated hurriedly by six Royal Navy ships at the request of Alderney’s government, following France’s surrender to Germany.

On an isle that has held allegiance to the crown since 1066, families who had loved and cared for their tranquil island with pride for generations were uprooted and relocated to safety in Glasgow and other cities of northern Britain. Eileen Sykes was a teenager when she was told she had to leave her home. “It was very much a rush, I was called early on the morning and we could only take what we could carry.”

Shortly after the islanders left, 3,000 German soldiers – double the original population – invaded the vacated island setting up four slave labour camps with several subsidiary camps. This tiny, isolated patch of grassland in the English Channel soon became a feared and heavily guarded Nazi prison camp. Upon direct orders of Adolf Hitler, Alderney became a strategic part of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall coastal defence system that stretched along the western edge of Europe.

The Germans brought around 6,000 slave labourers with them to the island to build the massive fortifications that were completed in an astonishingly short amount of time and on an unprecedented scale. Most of those sent to the camps were prisoners of war and civilians from Poland, Ukraine, Russia and other Soviet territories along with German and Spanish political prisoners. There were also hundreds of French Jews, incarcerated in huts separate from the rest of the prisoners and encircled by barbed wire.

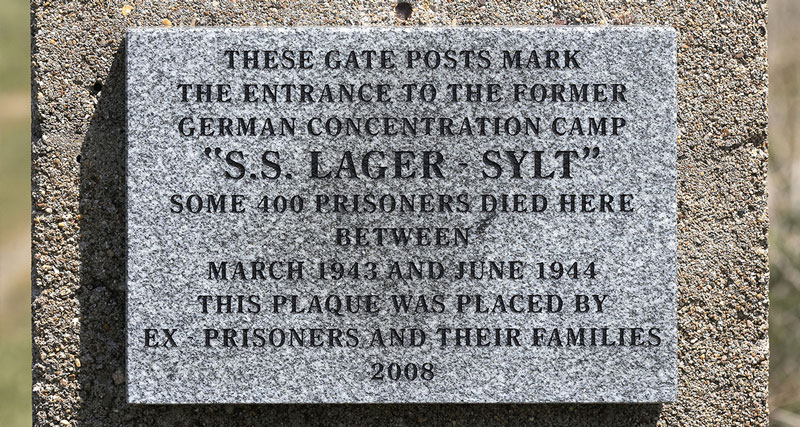

In 1943, two of the labour camps, Lager Sylt and Lager Norderney, were converted to concentration camps run by the “Death’s Head Unit” of the SS paramilitary.

Yet information about the scale of the SS operation and what happened to the victims on the island has remained largely unknown. Unlike the other islands in the occupied archipelago, such as Jersey and Guernsey where islanders had remained, there were no British witnesses eyeing the crimes taking place on Alderney. With no prying eyes of a civilian population monitoring activities, the Germans were left to do what they pleased for five years, with no concern for the brutal environment they were creating.

With the Germans destroying evidence of the camp before the island was liberated by British forces in 1945, and with reluctance from Westminster to fully reveal what had taken place on British soil, Alderney has been nicknamed, “the island of silence.”

But after eight decades of silence, recent archaeological discoveries, the release of undisclosed files and a renewed desire from campaigners is gradually revealing what really happened on Alderney.

Classified papers from Russia

The scale of the operation on Alderney has always been played down, but an investigative report by former top British army officers in 2017 claims the number of deaths was around 40,000-70,000, including many Jews.

One of the most significant reports on record was compiled by intelligence officer Captain Theodore Pantcheff for the British government, after Alderney was liberated. “Report on Atrocities Committed in Alderney, 1942-1945” was supposed to be locked away in British archives until 2045, but a copy was given to Moscow at the time due to the connection with so many Soviet victims.

It is only in recent years that researchers have discovered the document in the Russian State Archives. The paper makes solemn reading, but it casts light on one of the darkest events ever to take place on British territory.

In the classified report, Colonel Pantcheff recorded his own observations, spoke to German guards and prisoners, and obtained the testimonies of 3,000 witnesses. He describes the mass graves of the hundreds who were starved, beaten, tortured, or shot to death by the Nazis in what they called Vernichtung durch Arbeit- which translates as ‘extermination by labour’, issued by Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS.

One witness told Pantcheff that 300 to 400 Jews were buried in mass graves on Longis Common on Alderney.

It described how SS soldiers who were guarding the prisoners were rewarded with extra leave for “every five dead prisoners,” and shot prisoners for the smallest of offenses.

He wrote that a “common cause” of death in 1943 was starvation “assisted by physical ill-treatment and overwork.”

Pantcheff learned from prisoners that many inmates were killed as ‘sport’, using dogs to force prisoners through security fences only to be shot by SS guards. The SS documented many such executions as ‘suicides’. One witness told him the walls of Norderney commander Karl Theiss’s office were repainted “three or four times to remove blood stains.”

The gateposts were also a favoured place for the SS to perpetrate and display brutality. A former Norderney prisoner explained, “At Lager Sylt we saw a Russian, he was just hanging, strung up from the main gate.”

“On his chest he had a sign on which was written: ‘for stealing bread’. Others were left hanging for days and whipped or had cold water poured over them all night until they died.”

Colonel Richard Kemp, former commander of British Forces in Afghanistan, has also conducted independent research piecing together the conclusion that the severity of what took place was even greater than initially recorded in Pantcheff’s report. Writing about events on the island, he says, “They died not in hundreds but in their thousands and tens of thousands on Alderney. And when they dropped, they were replaced by others – who in turn were also worked to death and then replaced.”

With an average life expectancy of three months, turnover was rapid, says Kemp.

Further witnesses

Chilling details from witness statements of survivors, mainly Russians, that have emerged since the Pantcheff report was published, show how horrendous conditions really were.

“Two prisoners collapsed where they stood,” says one, “and to my horror they were thrown into the sea. Later that day, seven more went the same way. Throwing men over the cliff became the standard way of getting rid of exhausted workers.”

On another occasion, the survivor said he saw 50 slave workers shot and thrown into the sea with stones tied to their feet.

Former Sylt survivor Wilhelm Wernegau testifies how the camp’s cook was strangled by the SS because they did not like his food.

“Another man was crucified for stealing, hung by his hands. When I got up in the mornings I saw dead bodies in the bunks around me.”

“There was a special hut where the corpses were piled. Later they were taken away, loaded onto trucks and dumped in the sea.”

He also says that a special squad was deployed to fatally inject prisoners who were no longer strong enough to work.

Another survivor recalled 500 men dying there during his time alone. They were replaced from concentration camps in Germany such as Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen and Neuengamme.

Kemp says that knowing the precise number of victims will never be possible, but it is vastly bigger than has ever been suggested before.

“A minimum 40,000 slave labourers died from exhaustion, sickness, injury and brutality and perhaps as many as 70,000.”

“All this makes Alderney the scene of a massive war crime, its own mini-Holocaust, no less, which needs to be respected” says Colonel Kemp. “It is time this was finally recognised. The island is a mass grave, which needs to be respected.”

To this day, what the British government knows about what lies beneath the ground of Alderney hasn’t been made public, with criticism levelled against British authorities for pulling veils over the truth. Some argue Britain classed the 1945 report as confidential because few wished to dwell on the issue of mass killings and burials on the island. Others believe the British may have wanted to divert criticism from why the island wasn’t initially defended.

Earlier this year, Conservative MP Matthew Offord called on the UK government to release the undisclosed files about the mass graves.

He said, “We have a duty to ensure that no-one is left behind and I ask the Government to play its part and do the right thing by releasing all information and documents in its possession.”

New archaeology research

What remained after the German cover up was quickly overtaken by Alderney’s billowing long grass and abundant flora, fading the camps into the windswept landscape. But in recent years archaeologists have carried out extensive projects on Alderney, uncovering several remaining structures that were part of the Sylt camp.

Caroline Sturdy Colls, who is professor of conflict archaeology and genocide investigation at Staffordshire University in England, has spent more than ten years studying the Alderney camps. She says the physical traces of the atrocities committed at Sylt have been both “physically and metaphorically buried.”

“As a British citizen and a researcher, I hadn’t heard about the atrocities perpetrated on Alderney during World War II until I was doing my Ph.D. research,” says Sturdy Colls, “I had a wider awareness of the fact that the Germans occupied the Channel Islands, but not really that they built those camps.”

In a recent study, Sturdy Colls and her team combined archival records with modern forensic methods such as ground-penetrating radar. To avoid digging, the team used Lidar, which uses lasers to map large areas, attaching it to a drone through which they found physical evidence supporting witness accounts of harsh conditions at Sylt. They mapped the surviving shallow depressions of the barracks at the camp, confirming witness reports of overcrowding. Each prisoner had just 16 square feet (1.5 m2) of space at best. The team made virtual-reality visualisations for a clearer view of features.

Using aerial images, the researchers also tracked how both the size and security measures of Lager Sylt drastically increased when it evolved from a labour camp to a concentration camp in 1943.

“We’re not the first people to discover this camp existed—but despite all those testimonies and despite all those previous efforts, the history of the site was still not known,” Sturdy Colls says.

“The work we did was trying to help the stories of the people who suffered be known more widely.”

Chemical weapons?

Away from the world’s attention, the secrecy afforded by occupied Alderney has raised speculation about a further sinister role. The takeover by the notorious SS on Alderney – and nowhere else in the Channel Islands – in place of operational German command has only added to the mystery.

In 2017, Colonel Richard Kemp and John Weigold visited Alderney and conducted a survey of the land and remaining evidence, including the miles of complex system of tunnels stretching deep underground, hewn out of bare rock by the slave labour force of concentration camp inmates.

Combining their experience and expertise in military construction, terrain and logistics, Kemp and Weigold ruled out previously held theories behind the purpose of the tunnels and made a shocking discovery.

“We have uncovered incontrovertible evidence that a top-secret launch site for V1 missiles…was being constructed on the island,” they said.

The V1, the doodlenug, was the prototype for today’s cruise missiles, with which Hitler intended to devastate England.

The reason for the secrecy was that they were to be armed not with conventional explosives, but with internationally outlawed chemical warheads, including nerve agents Sarin and Tabun. The pair say they had not seen anything like it in northern Europe. They calculated that the tunnels could have housed as many as 72 missiles at one time.

They could even pinpoint their potential targets by the direction of the rocket launch ramps. It suggests the target for the bombs was along the southern coast of England from Weymouth to Plymouth, where in late 1943 and 1944 hundreds of thousands of British and American troops prepared for the D-Day invasion.

“If the Alderney missiles had been fired – and our conclusion is that they were within a whisker of this happening – their chemical payloads would have thrown Allied invasion plans into such chaos that D-Day could not have taken place on June 6, 1944, and the whole course of World War II would have been drastically altered.”

They suggested it would have put the Allies on the back foot, and might even have allowed Hitler to fulfil his ambition to conquer Britain.

“We came to the conclusion, with other factors, that this is why they were sited in Alderney, because you could construct and prepare V1’s with nerve agent warheads on them, which you could do in total secrecy given the unique circumstances of Alderney, there was no possibility of anyone discovering it,” Colonel Kemp said.

The research seems to confirm eye-witness reports, including one of chemical canisters being unloaded onto the island and frequent gas drills where German soldiers wore masks for a whole day at a time – even on the heads of their horses – but not the prisoners.

“In our professional military capacities, we are well versed in aspects of chemical weaponry…What we are now sure is that Alderney had a fully developed secret V1 site for missiles loaded with deadly nerve agent.”

Homecoming

The reinforced bastion of Alderney was the last of the Channel Islands to be liberated, nine days after VE Day. The people of Alderney could not immediately return to the island due to the removal of over 30,000 landmines. But when the first islanders began to return, it was a very different island to the one they had left.

Today a simple plaque, only installed in 2008 at the request of former prisoners, can be found on a remaining gatepost among overgrowth at the entrance of the Lager Sylt camp.

In 2017, the Alderney government formally designated Lager Sylt a conservation area, barring development that would threaten the site. Colonel Kemp believes Alderney’s unique history would qualify it as a world heritage site to protect it at all costs, and should feature a Holocaust memorial.

But how the legacy of the concentration camps on Alderney under Nazi occupation should be remembered is still a matter of debate on the island.

In July 2021, a delegation from the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) visited the island, meeting with Alderney’s government and members of the community to discuss ways to safeguard the sites, including proper signage, an exhibition, educational materials for schools, as well as proper boundary marking of the Longis Common burial ground.

“There is still a small group of people who want to put the past behind them and continue without looking into it too much,” Graham McKinley, an Alderney legislator told National Geographic. “I believe we should be doing a lot more to show the world what actually happened here.”

On our doorstep

Like its rugged cliffs sustaining a cycle of crashing waves, this peaceful island will continue to stubbornly hold tight to its hidden past without ever giving us a complete picture of what took place there. What more can this little island tell us that will bring some respectful closure to the people who suffered there?

These findings remind us just how close the Nazis came to the shores of mainland Britain. Not only did the Nazis occupy the Channel Islands, they had turned innocent Alderney into a fortress of evil in preparation for invasion.

It compels us to be thankful for the sacrifice that was made by British troops and our allies to prevent the stronghold of Alderney from extending further into our isles with devasting consequences. But it is with a sense of regret that we wonder how it took so long to properly acknowledge the magnitude of atrocities that took place on our very doorstep, and why to this day the truth remains largely buried.

We must continue to pursue answers for the sake of the memory of the victims, for the relatives of loved ones who perished there, for truth about what took place against Jews and others in the Holocaust, and on behalf of the islanders who were displaced.

And to fully appreciate the cost of those who gave their lives, we must understand the extent of wickedness that was ultimately defeated. Meanwhile, we look to a day when the things that are hidden will be exposed.