This article first appeared in the CUFI UK Torch Magazine. For the latest issue, see here.

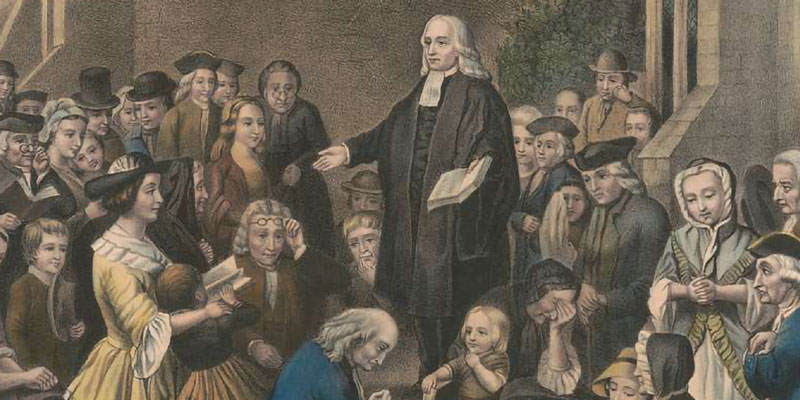

Mention John and Charles Wesley and perhaps the first things that come to mind include the founding of Methodism, or the thousands of treasured hymns penned by Charles, or perhaps John’s preaching of revival and reform that swept across the British Isles. Or maybe you think of the thousands of small Wesleyan chapels dotted across the English landscape, or even what became a huge global movement with denominations worldwide.

But did you know that John and Charles Wesley were Zionists? It maybe shouldn’t surprise us; after all, “rightly dividing the Word of Truth”, as the Apostle Paul advised Timothy, will always lead us to a clear understanding of God’s wisdom, including His purpose for Israel. The principle of placing the Bible as our foundation is very much needed today, both personally and at the heart of the Church. Many Christians who have been blessed by the Methodist Church will have been saddened by the recent anti-Israel motions passed at its annual UK gathering. But it doesn’t reflect the legacy of its founders and the beliefs they championed.

Building bridges with Jews

Born in 1703 and 1707 respectively, John and Charles were Anglicans their whole lives, having been ordained at Oxford University. It was in Oxford that the brothers and other students at Oxford formed a small group dedicated to frequent Communion, serious study of the Bible, and regular visitations to the deprived Oxford prisons. The members of this group, which the Wesleys came to lead, became known as Methodists, because of their “methodical” devotion and study.

In 1735, John sailed across the Atlantic to the New World with the intention of being a missionary to the indigenous tribes. Arriving in the colony of Georgia, John’s mission took a different direction, such is the Scripture, “a man’s heart devises his way, but the Lord directs his steps”!

John spent most of his time ministering to the needs of colonists in the town of Savannah. Whilst the majority of residents were Gentiles, around 15-20 per cent of the community were Jewish. The experience made a significant impression on John and Christian immigrants in Savannah. Many Christians at the time had been conditioned to view Jews with suspicion and distrust because of the damage caused by rooted anti-Semitic attitudes. But what the Christian immigrants experienced in Savannah was much different to the widespread conspiracies. In fact, when Christian immigrants arrived they were met by Jews presenting them with gifts of food. Jews and Christians also forged friendships by gathering at one another’s respective occasions.

John Wesley himself recognised the importance of serving the Jewish community in Savannah alongside its Christians, without a hidden agenda. He had begun learning a little Spanish to help in his role as a translator for a high-ranking British colonel, General Oglethorpe, who had founded the colony of Georgia. But when this ended, Wesley continued the Spanish language studies so that he could better converse with, what he called, his “Jewish parishioners”.

The Portuguese Jew

One of those parishioners was Dr Samuel Nunez Ribeiro, a Jewish physician of Portuguese descent. Shortly before Wesley’s arrival, London had expressed concern about Georgia becoming a ‘Jewish colony’, but General Oglethorpe allowed Jews to settle in Savannah. At the time, the town was suffering under a raging uncontrollable epidemic, understood to be Yellow Fever, that had even killed the community’s only doctor. Dr Nunez, an expert in infectious diseases, insisted that he could help. To the amazement and appreciation of the Christians in Savannah, Dr Nunez ended the epidemic and word soon spread to London of how the Christians in Savannah had been blessed by the Jewish doctor.

Like many Jews in Savannah, Dr Nunez had a story. Born in Portugal during the Portuguese Inquisition, his parents were the descendants of Marrano Jews who had been forcefully converted to Roman Catholicism under pain of banishment. While publicly Catholic, he was secretly raised as a Jew. He trained in medicine and had a lucrative practice in Lisbon as one of the most successful doctors in Portugal at an unusually young age. He was physician to the King of Portugal and other nobility, including the Grand Inquisitor of Portugal and members of the Dominican Order. While conforming to Catholicism in pubic, he and his wife practiced Judaism in private. He also secretly converted several back to the Jewish faith from Catholicism. Then one day a secret agent, posing as a servant, reported that the family were visiting an underground synagogue and they were arrested during a Passover service. They were tortured whilst in prison but saved by intervention by the Grand Inquisitor so that he could be medically treated by Dr Nunez.

As part of the agreement, Nunez was under full-time surveillance with two inquisition officials present at all times. But in 1726 the pressure became too great. A daring escape plot involved Nunez hiring an English captain to bring a ship to the port and inviting the doctor and his entire family as guests on board, something quite normal in Lisbon’s high society. An hour later the ship started to sail to England with the two unknowing inquisition officials on board!

In England, Nunez was circumcised, and the family changed their first names. Then he and his wife held a Jewish wedding ceremony.

This was the aging Dr Nunez who John Wesley met and became good friends with in this complex colonial town. The Christian preacher from England would spend many evenings sitting in the company of this trialled Portuguese Jew. How gracious it was for this Jewish doctor, having been tortured and banished – and his ancestors likewise – in the name of so-called Christianity by fanatics failing to represent anything like the character of Christ, to willingly befriend and accommodate this young roaming missionary who had landed in a world much different to the one he had left behind.

We understand from Wesley’s diaries that he frequently visited Dr Nunez, enjoying the conversation and opportunity to relax. One commentator says Nunez had “kept his door open” for Wesley and provided a “haven to which Wesley could retire, at least temporarily.” Initially helping Wesley with Spanish, the language lessons soon made way for deep, lively discussion on an array of topics. Wesley was fascinated with Nunez’s medical knowledge and particularly the care he gave all his patients. Their topics briefly touched on theology, but ultimately their relationship transcended the religious differences between them.

Little did either know that Dr Nunez and the Jews of Savannah would soon be displaced yet again to escape the threat of Spanish take-over.

Wesley left Savannah abruptly due to a disagreement with a colonial leader, but his first – and probably only – encounter with a Jewish community made a lasting impact. Writing in his diary in Savannah, Wesley went so far as to note that “Jews in his parish, ‘seemed nearer to the mind that was in Christ than many who call him Lord.’”

All or nothing

John Wesley returned to England two years later, in 1737, different to the man that had left. Not only had John become a staunch abolitionist, but he also returned with an “all or nothing” kind of Christianity. He taught that one either believed entirely, without a shadow of reservation or doubt, in salvation through absolute faith alone, made possible by God’s grace, or one was simply not a Christian at all. Whilst in the American colonies, he had also been impressed by the pious practices of the Moravian movement that resonated with his existing “methodical” ideas of devotion and study.

Unapologetically holding the belief that the Anglican church needed reform from within, Wesley had to resort to preaching open-air or in barns and other temporary locations.

Criticism

Wesley developed a view that the Jews he encountered at home had drifted far from the “God of their Fathers, the God of Israel” and were no longer listening to “Moses and the prophets”. Some might consider this out of place for Wesley, to make such assumptions and perhaps not helpful in a society that already took a negative view of Jews, but defenders note that he never held the Jewish people to a higher standard than Christians. In fact overwhelmingly quite the opposite, focusing more on highlighting the shortcomings of Christians, the importance of self-examination and the need for reformation in the Church. Despite language that might not be palatable today, underpinning Wesley’s motives was a sincere and passionate longing for the Jewish people to connect with the God of their forefathers, perhaps in much the same way as his good Jewish friend Dr Nunez had done against such tremendous persecution. For Wesley firmly understood God’s plan for Israel and never attempted to deny or downplay the special place that Jehovah has for the Jewish people. The heretical themes of replacement theology so prevalent today were never uttered from Wesley’s pulpit.

Assurance of faith

Even Wesley himself was not exempt from his own self-examination. It was in 1738, upon his return to England, that Wesley, reflecting on his own spiritual condition, had a “conversion experience” at a service at Aldersgate, London about which he recorded, “I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine and saved me from the law of sin and death.”

Charles had a similar experience around the same time, and together the Wesley brothers turned a spontaneous movement into a structured body that would later become the Methodist Church, shortly after their deaths. Whilst John preached and organised the movement, Charles famously penned over 6,500 hymns. And it is by sampling the truth imparted through their lyrics that we truly get an insight of the Wesley’s love for Zion and the Jewish people. Let’s take a look at some examples.